Mark 16:9-20 as Forgery or Fabrication

by Richard Carrier, Ph.D. (2009)

Honest Bibles will tell you (in a footnote at least) that in the Gospel according to Mark all the verses after 16:8

are not found in "some of the oldest manuscripts." In fact, it is now

the near unanimous agreement of experts that all those verses were

either forged, or composed by some other author and inserted well after

the original author composed the Gospel (I'll call that original author

"Mark," though we aren't in fact certain of his name). The evidence is

persuasive, both internal and external. In fact, this is one of the

clearest examples of Christians meddling with the manuscripts of the

canonical Bible, inserting what they wanted their books to have said

(and possibly even subtracting what they didn't want it to have said,

although I won't explore that possibility here). For the conclusion that

those final verses were composed by a different author and added to

Mark is more than reasonably certain.

If Mark did not write verses 16:9-20, but some anonymous person(s) later added those verses, pretending (or erroneously believing) that Mark wrote them (as in fact they must have), then this Gospel, and thus the Bible as a whole, cannot be regarded as inerrant, or even consistently reliable. Were those words intended by God, he would have inspired Mark to write them in the first place. That he didn't entails those words were not inspired by God, and therefore the Bible we have is flawed, tainted by sinful human forgery or fallibility. Even the astonishing attempt to claim the forger was inspired by God cannot gain credit.1 For it is so inherently probable as to be effectively certain that a real God would have inspired Mark in the first place and not waited to inspire a later forger. The alternative is simply unbelievable. And in any case, a lie cannot be inspired, nor can a manifest error, yet this material is presented as among that which is "according to Mark," which is either a lie or an error.

This has a further, even greater consequence. Since we are actually lucky the evidence of this meddling survived, we should expect that other instances of meddling have occurred for which the evidence didn't survive, calling into doubt the rest of the New Testament (hereafter NT). Since the survival of evidence is so unlikely for changes made before c. 150 A.D. (fifty to eighty years after the NT books were supposedly written), and in some cases even for changes made before c. 250 A.D. (well over a hundred more years later)—as we have few to no manuscripts of earlier date, and none complete, and scarce reliable testimonies—we can expect that many other changes could have survived undetected.2 And yet alterations in the earlier period are the most likely. For when the fewest copies existed, an emender's hope of succeeding was at its greatest, as well as his actual rate of success. Such was the case for all other books, so it should be expected for the Gospels. As Helmut Koester says, "Textual critics of classical texts know that the first century of their transmission is the period in which the most serious corruptions occur," and yet "textual critics of the New Testament writings have been surprisingly naive in this respect," despite the fact that they all agree "the oldest known archetypes" we can reconstruct from surviving manuscripts "are separated from the autographs by more than a century."3

The interpolation of the Markan ending thus refutes Biblical inerrancy. As Wilbur Pickering put it:

Only the most convoluted and implausible system of excuses for God can escape this conclusion, and any faith that requires such a dubious monstrosity is surely proven bankrupt by that very fact.

The transition is not only ungrammatical, it is narratively illogical. Verse 9 reintroduces Mary Magdalene with information we would have expected to learn much earlier (the fact that Jesus had cast seven demons out of her). Instead it is suddenly added in the LE, completely out of the blue without any explanation, suggesting the author of the LE was trying to improve on the OE or wasn't even writing an ending to Mark but a separate narrative altogether (in which this is the first time Mary Magdalene appears in this scene or in which the story of her exorcism appeared many scenes earlier). Either entails that the same author did not write the OE. Indeed, it makes no sense to add this detail in the LE, as it serves no narrative function, adds nothing relevant to the story, and alludes to an event that Mark never relates. If the author of the LE were Mark, he would have added this exorcism story into the narrative of Jesus' ministry, and then alluded to it (if at all) when Mary Magdalene was first introduced in verse 15:40, or when she first appears in the concluding narrative (verse 16:1). Furthermore, not only does the subject inexplicably change from the women to Jesus, but suddenly Mary Magdalene is alone, without explanation of why, or to where the other two women have gone.

We should also expect some explanation of when these appearances occurred, yet we get instead an inexplicable confusion. Verse 9 says they happened after Jesus rose on the first day of the week, but it's then unclear as to how many days after. This single temporal reference would normally entail everything to follow occurred on the same day. But that would contradict the OE's declaration that Jesus had already gone ahead to Galilee and would appear there, as it would have taken several days for the women (or anyone else) to travel from Jerusalem to Galilee. It is unlikely Mark would produce such a perplexing contradiction or allow a distracting ambiguity like this in his story, as he is elsewhere very careful about marking relevant chronological progression (e.g. Mark 16:2, 15:42, 14:30, 14:12, 6:35, 4:35, etc.). Mark also wouldn't repeat the declaration that it was "the first day of the week," as he already said that in verse 16:2. Instead, he would simply say "on the same day," or not even designate the day at all, as there would be no need for it (his narrative would already imply it), until the story entailed the passage of several days (perhaps either at 16:12 or 16:14). Apparently the author of the LE assumes the day hasn't yet been stated (and thus appears unaware of the fact that it was already stated in the OE only a few verses earlier) and then assumes all these events took place over a single day, and thus in and around Jerusalem, which contradicts Mark's declaration that the appearances were to occur in Galilee (16:7, 14:28, corroborated in Matthew 28:16-20), yet conspicuously agrees with Luke and John (a telling contradiction that will be discussed later).

All four oddities (the incorrect grammar, the strange reintroduction of Mary, the unexplained disappearance of the other women, and the chronological redundancies and contradictions) make the transition from the OE to the LE too illogical for the same author to have written both. On the hypothesis that the LE was written by another author in a different book and just copied into Mark by a third party, all these oddities are highly probable. But on the hypothesis that Mark wrote the LE, all these oddities are highly improbable. Indeed, any one of them would be improbable. All of them together, very much so.

A similar structure accompanies Mark 6:45: the subject is already established as Jesus at 6:34, then Jesus gives commands to his Disciples to deliver food to the multitude (6:37-39), and in result the multitude eat (6:40-44), thus temporarily becoming the subject, then Jesus gives another command to his Disciples (6:45). The nested structure already has the subject clearly established as Jesus. So there is no parallel here to 16:9. The same structure accompanies Mark 7:31: the subject is already established as Jesus at 7:6, then Jesus teaches and interacts with the crowd, then heads toward Tyre and enters a house (7:24), then a woman begs his aid and they have a back-and-forth conversation (7:25-30), in which the subject shifts entirely as expected from her (7:26) to him (7:27) to her (7:28) to him (7:29) to her (7:30), and then back to him (7:31). The woman has departed in verse 7:29, so obviously we expect the subject at 7:31 to pick back up with who the primary subject has been all along: Jesus. Mark even indicates this by telling us he "again" went toward Tyre (thus leaving no mistake who the subject is). Again, there is no parallel with 16:9. In just the same way, at 8:1 we already know Jesus is the subject: he is the subject all the way up to 7:36, then we hear a brief audience reaction at 7:37, then Jesus is again the subject at 8:1, as we should already expect. In a comparable fashion, at 14:3 Jesus has already been the primary subject throughout chapter 13, then is temporarily the subject of conversation for just two verses (14:1-2), then becomes the primary subject again (14:3). There is no comparable nested structure at 16:9.

Moreover, all these alleged parallels show how different the style of the LE is, as Mark uses kai ("and") dozens of times to mark almost every transition in Mark 2 (19 out of 28 verses begin with kai), 6 (40 out of 56 verses begin with kai), and 7 (18 out of 37 verses begin with kai), yet the author of the LE shows no comparable fondness for kai (apart from two un-Markan transitions with kakainos, he begins only 1 of 12 verses with kai, and this despite the fact that the LE runs through no fewer than 9 comparable sentence transitions in just 12 verses), and more importantly, he doesn't use it to transition in 16:9, as we would expect if this is supposed to parallel the Markan style of 2:13, 6:45, 7:31, and 14:3 (which all transition with kai) as Terry claims. Only 8:1 uses instead the device of a participle-verb construction similar to 16:9, yet doesn't transition with the particle de. The LE does. And again, the subject of 8:1 was already established two verses earlier, in an obvious nested structure not at all parallel to 16:9. Another stylistic oddity comes from another verse that Terry mistakenly considers a parallel: only once, he says, does Mark elsewhere begin a new pericope with a participle, and that's at 14:66, which he claims is a parallel for 16:9. But in fact 14:66 begins with a genitive absolute, which is indeed a very Markan feature (it's also how he transitions in 8:1, another of Terry's alleged parallels). It's just that this is exactly what the author of the LE doesn't do at 16:9. Since 16:9 does not use the genitive absolute to mark its transition, but 14:66 does, even 14:66 fails to be a parallel, but instead shows just how different Mark's style was from the author of the LE.

Even the cursory temptation scene (Mark 1:12-13) is no comparison. It still reads like a complete unit, for which we would not need or expect any further details had we not otherwise known of them (from the expansion of Matthew and Luke). The LE, by contrast, is unintelligible without knowing the details alluded to, and is not a single event, but a long compressed series of them. Never mind that each one is of phenomenally greater narrative importance than the relatively trivial fact that Jesus was once tested by the Devil. What remains inexcusably peculiar is the great number of events, compressed to so small a space—compressed so far, in fact, that each one bears even less detail than the temptation, and what details got added make no inherent sense (as will be shown in section 4.3.1). Moreover, Mark composed a unified Gospel from beginning to end, so if Mark had written the LE, we would expect the LE to mention Galilee: he has set this detail up twice already (14:28 and again in 16:7), anticipating an appearance in Galilee. So that he would drop this theme in the LE is inconceivable. Indeed, as observed in section 4.1.1 (above), the LE not only drops that theme, it contradicts it by evidently presuming a series of appearances in and around Jerusalem.

Certainly, any single deviation of style will occur at the hand of the same author in any passage or verse, sometimes even several deviations of different kinds, and unique words will be common when they are distinctive to the narrative. But to have so many instances of so many deviations in such a short span of verses (against a compared text of hundreds of verses) is so improbable there is very little chance the LE was written by the same author as the rest of Mark. And the above list is but a sample. There are many other stylistic discrepancies besides the twelve just listed (and the others in section 4.1.2 above, which must be added to those twelve). James Kelhoffer surveys a vast number of them in MAM (pp. 67-122).

As Darrell Bock says, "it is the combination of lexical terms, grammar, and style, especially used in repeated ways in a short space that is the point." Hence appealing to similar deviations elsewhere in Mark fails to argue against the conclusion, which carries a powerful cumulative force matched by no other passage in Mark. This is emphasized by Daniel Wallace:

The SE is even more incongruent with Markan style. Despite being a mere single verse, 8 of the 12 words in it "that are not prepositions, articles, or names" are never used by Mark—but half of them are found in the Epistles (and sometimes, among NT documents, only there).21 The whole verse consists of just 35 words altogether, 9 of which Mark never uses, in addition to several un-Markan phrases (including, again, meta de tauta). Discounting articles and prepositions and repeated words, the SE employs only 18 different words, which means fully half the vocabulary of the entire SE disagrees with Markan practice. Half the SE also consists of a complex grammatical structure that is not at all like Mark's conspicuously simple, direct style. You won't find any verse in Mark with the convoluted verbosity of "and after these things even Jesus himself from east and as far as west sent out away through them the holy and immortal proclamation of eternal salvation." The SE was clearly not written by Mark.

In contrast, almost none of Terry's 'examples' are generic phrases—and what generic structure we can discern among them is often confirmed in Markan style elsewhere. For example, he claims "now evening having come" (êdê opsias genomenês) is a unique 'phrase' but what's actually generic in this phrase is êdê [x] genomenos, "now [x] having come," which Mark uses two other times (Mark 6:35 and 13:28). So this is not unique in 15:42. Likewise, Terry claims "know from" (ginôsko apo) is a unique phrase, but it's not, as Mark 13:28 has "learn from" (apo mathete), the exact same grammatical construction, just employing a different verb, while the same verb was not unknown to Mark (who used it at least three times, just never in a context that warranted the preposition). Meanwhile, "roll on" (proskulio epi) isn't a generic phrase at all—it's just an ordinary verb with preposition, and Mark uses verbs with epi to describe placing objects on things quite a lot (e.g. Mark 4:5, 4:16, 4:20, 4:21, 4:26, 4:31, 6:25, 6:28, 8:25, 13:2, 14:35), so there is nothing unique about that here, either. And there is nothing generic whatsoever about "the door of the tomb" or "white robe." These are highly specific constructions, using established Markan words. For leukos ("white") and stolê ("robe") appear elsewhere in Mark, and mnemeion ("tomb") appears two other times in Mark (and the equivalent mnêma twice as well), and thura ("door") likewise appears four other times. Likewise, "be not afraid" (me ekthambeisthe) is not a generic clause, but a whole sentence (it is an imperative declaration), none of which is unusual for Mark, who routinely uses mê for negation and uses the exact same verb (ekthambeô) in 9:15. Similarly, "come very early" (lian prôi erchomai) is not a generic phrase, either, it's just a verb with a magnified adverb of time, nor is it an unusual construction for Mark, who has "go very early" (lian prôi exerchomai) in 1:35, and who otherwise uses prôi and lian several times, and erchomai often.

That leaves only two unusual phrases in verses in 15:42-16:6: mia tôn sabbatôn, literally "on the first [day counting] from the Sabbaths" (i.e. "first day of the week") and en tois dexiois ("on the right"). The former simply paraphrases the Septuagint (Psalm 24:1), which Mark is known to do (e.g. Psalm 22 all throughout Mark 15:16-34). Only the latter is very unexpected as Mark otherwise (and quite often) uses ek dexiôn to say "on the right." So these two phrases are unique to 15:42-16:6. It's just that 2 unique generic phrases in 12 verses is simply not enough to doubt their authorship (especially when one is a quotation). But 9 unique generic phrases definitely is, especially in conjunction with all the other deviations: the Markan vocabulary that's missing, the non-Markan vocabulary that's present, the un-Markan frequencies of Markan words, and the un-Markan idioms where Mark has established a completely different practice. It is all these oddities combined that makes for a vanishingly small probability of Markan authorship. Indeed, if this is not enough evidence to establish the LE wasn't written by Mark, then we should just assume everything ever written in the whole of Greek history was written by Mark.

Of course, such agreement can also be found by mere chance between any two authors. But it's even more likely when a later author has been influenced by the earlier one, and an author familiar with the whole NT could easily exhibit influence from all its authors, Mark included. This would be all the more likely if the author of the LE deliberately attempted to emulate Markan style (as a forger would be inclined to do), but if that was his intent, his effort was marvelously incompetent. For as we've seen, the disagreements of style are so enormous they far outweigh any agreement there may be. In fact, the deviations are so abundant and clear, they could argue against the original author of the LE intending it to be used as a forgery (if we assume a forger would do better). The 'forger' would then instead be some additional third party who attempted to pass off the LE as belonging to Mark. It's also possible the LE became attached to Mark by accident. But the SE can only have been a deliberate forgery, yet it deviates as much or more from Markan style, so being a lousy forgery is evidently not a valid argument against forgery. Nevertheless, I have already presented evidence (in section 4.1 above) and will present more (in following sections) that, more probably, the author of the LE did not write it as an ending to Mark but as a harmonizing summary of the appearances in all four Canonical Gospels, originally in a separate book (quite possibly a commentary on the Gospels), which was simply excerpted and attached to Mark by someone else (whether deceitfully or by accident).

James Kelhoffer (in MAM, esp. pp. 48-155) has already extensively proved the LE used the other three Gospels (and Acts) and has refuted every critic of the notion. I will only summarize some of the evidence here. But from this and all that Kelhoffer adds, it's very improbable these elements would exist in the LE unless the author of the LE knew the Canonical NT and intended his readers to have access to it themselves.

The only element of the LE that doesn't derive from the other three

Gospels is the remark about 'drinking deadly poison' without effect.

Papias claimed it was being said several generations after Mark that

Justus Barsabbas (of Acts 1:23)

drank poison without harm "by the grace of the Lord," the only

(surviving) reference to such a power in the first two centuries.23 How that would influence the LE is anybody's guess. But the LE's claim is more likely an inference from Luke 10:19, in which Jesus says "I have given you authority to tread upon serpents and scorpions, and over all the power of the enemy, and nothing

shall in any way hurt you" (emphasis mine), which would certainly

include poisons, especially given the juxtaposition of immunity to

poisonous animals. Luke mentions scorpions and snakes; the LE, snakes and poison; hence the substitution would be an easy economization of the whole thought of Luke 10:19 and a typical example of the composition skills ancient schools inculcated.

The LE thus looks unmistakably like a summary of Matthew, Luke, Acts, and John—particularly Luke-Acts and John (whose styles also influenced the vocabulary and grammar of the LE, as noted in section 4.2), which are notably the two last Gospels to be written, and only ever logically found together in the canonical NT. And conspicuously, only these four Gospels are aped here, not a single other Gospel, despite there being many dozens to choose from. Which is practically a giveaway: the LE author is simply summarizing (and briefly harmonizing) the NT Gospels. Contrary to a common assumption, there is evidence that the traditional canon was assembled in codex form already by the mid-2nd century (even though not yet declared the official NT by any particular authority).24 But that's still long after Mark would have died. One element is a near giveaway: the phrase 'two of them' (16:12) is verbatim: duo hex autôn, "two of them," in fact a very unusual way to say this, yet found verbatim in Luke 24:13, the very story being alluded two here. That suggests direct influence from Luke's actual narrative. Kelhoffer (in MAM, pp. 140-50) adduces many more direct lifts from Luke-Acts and the other Gospels.

In fact, the LE would make no sense to a reader who had no access to the NT. Why is Mary suddenly alone? How did Jesus appear to her? Where? What did he say? Who are "the two men" and why are they traveling in the country? Where are they going? And what is meant by Jesus appearing "in a different form," and why does he appear in that way only to them? Why in fact are there only "the eleven"? It's commonly forgotten that Mark never narrates or even mentions Judas' death, nor specifically describes him as expelled from the group or in any other way less likely to see the risen Jesus (as 1 Corinthians 15:5 implies he did), so if Mark were the author of the LE, his narrative would be inexplicably missing a major plot point. The LE clearly assumes familiarity with the NT explanations of Judas' death and thus his absence at the appearance to the Disciples (e.g. Acts 1:17-26), and is obviously alluding to the appearance of Jesus to Mary Magdalene in John (a story not told in Matthew or Luke) and to the appearance of Jesus in disguise to Cleopas and his companion on the road to Emmaus in Luke (a story not told in Matthew or John). To a reader unfamiliar with those tales, the LE's narrative is cryptic and frustratingly vague, and essentially inexplicable. Why would anyone write a story like that? Only someone who knew the other stories—and knew his audience would or could as well.

The LE is not only a pastiche of the other Gospel accounts, it's also an attempt at harmonization. To make the narrative consistent, the LE's author did not incorporate every element of the canonical stories (which would have been logically impossible, or preposterously convoluted). He also deliberately conflates several themes and elements in the interest of smoothing over the remaining contradictions, giving the appearance of a consistent sequence of events—and forcing the whole into a narratively consistent triadic structure (examined below). This kind of harmonizing pastiche exemplified by the LE is an example of the very practice most famously exemplified in Tatian's Diatessaron (begun not long after the LE was probably composed), which took the same procedure and scaled it up to the entire Gospel (only copying words verbatim rather than writing in his own voice). Kelhoffer (in MAM, pp. 150-54) discusses other examples, demonstrating that the LE fits a literary fashion of the time.

Instead, the LE appears to be a coherent narrative unit inspired by the NT. It depicts three resurrection appearances, in agreement with John 21:14, which says Jesus appeared three times. And all three appearances have a related narrative structure: all three involve an appearance of Jesus (16:9, 16:12, 16:14), followed by a report or statement of that fact, always to the Disciples (16:10, 16:13, 16:14), which the first two times is met with unbelief (16:11, 16:13), while the third time the Disciples are berated for that unbelief, when Jesus finally appears to them all (16:14). This running theme of doubt also appears in the other Gospels, but in entirely different ways, showing no cognizance of the LE (Matthew 28:16-17, Luke 24:10-11 and 24:36-41, and John 20:24-28). The author of the LE clearly intended to harmonize the three other accounts by merging them together in a semblance of a coherent sequence, a sequence that makes no sense except at the hands of someone who knew the three other Gospels and had in mind to unite and harmonize their accounts while glossing over their discrepancies.

One might hypothesize that this shared theme of doubt, as well as other shared themes (e.g. Mark 16:15-20 summarizes the "commission" theme present in the other three Gospels: Luke 24:46-47, John 20:23, Matthew 28:18-20), indicates the LE was the source for the Gospels. But that does not fit. Those later authors must have each chosen coincidentally to drop entirely different elements from each other, and to completely rewrite the rest, all in a different order, and in consequence repeatedly and irreconcilably contradicting Mark. Which all makes far less sense than the opposite thesis, that the author of the LE was harmonizing their accounts after the fact. The LE also lacks the details that are necessary to make sense of each story, and thus assumes those details were already in print. So the LE more likely abbreviates the Gospel narratives. Those narratives are far less likely to be embellishing the LE. Moreover, the LE summarizes the appearances and events in all of the Gospels, whereas none of those Gospels used all of the LE, but each (we must implausibly suppose) must have chosen different parts to retain. Instead, they seem unaware of the other appearances and events related in the LE. It's thus improbable that the Gospels used the LE (but conveniently left out exactly those stories that the other Gospels left in, completely altered what they included, and sharply contradicted Mark in the process) but very probable that the LE used the Gospels (smartly changing or leaving out the details that contradict each other). The result, as noted, is a situation in which none of the Gospels follow the LE even in outline, while the LE follows all three Gospels, though only as closely as is logically possible, assembling all their diverse stories into a single narrative. The coincidence is unbelievable on any other theory.

In his first example (Mark 1:32-39, cf. Black, PEM, pp. 68-69) many of the parallels Robinson adduces are specious (i.e. one must stretch the imagination to see a meaningful connection) and few make any literary sense (i.e. there is no intelligible reason for the parallels and reversals being alleged), while any connections we might expect to exist on his thesis (e.g. resisting serpents and poisons, the role of laying on hands, the significance of baptism, the theme of doubt, the first day of the week, appearing "in a different form," etc.) are all absent. Not that all of these would be expected, of course, but some at least should be, e.g. Robinson's claim of an earlier parallel use of exorcism and healing entails that the matching third component (immunity to poison) should be present. Otherwise the ending does not match the beginning. All we have are generic elements repeated throughout Mark and the whole NT.

There is a better case to be made that Mark 16:1-8 reverses 1:1-9, which would instead argue that verse 8 is the original ending—as framing a story this way (ending it by reversing the way it began) was a recognized literary practice of the era (called ironic inclusio), and would neatly explain many of the peculiar features of the OE (as a manifestation of irony, a device Mark uses repeatedly), making them intelligible, in exactly the way Robinson's theory does not make 16:9-20 any more intelligible in light of 1:32-39. This is not to argue here that Mark did end at verse 8, only that Robinson's thesis is less plausible than applying his own method to arguing Mark did end at verse 8.25

Similarly Robinson's attempt to see parallels elsewhere in Mark (in Black, PEM, pp. 70-72) are either contrived ("appointing the twelve" is supposed to parallel "appearing to eleven" even though neither verb nor number are the same; Mark 6:13 refers to healing by anointing with oil, not laying on hands, which actually argues against the connection Robinson claims), or simply erroneous (e.g. he mistakenly claims Mark 3:15 contains a reference to healing). The features he claims as parallels are also nonsensically out of order and lack any of the precise cues typical of Mark's practice of emulation. As with Robinson's first hypothesis, none of the features actually peculiar to the LE (e.g. immunity to poisons, damning the unbaptized, appearing "in a different form," etc.) are explained this way, whereas every feature (these and the ones Robinson singles out) are already explained (and explained much more plausibly, thoroughly, and accurately) by the triadic harmonization thesis.

I am normally quite sympathetic to the kind of analysis Robinson attempts, but his applications fail on every single relevant mimesis criterion (order, density, distinctiveness, and interpretability). The patterns he claims to see simply aren't there. There are only generic elements ubiquitous throughout early Christian and NT literature. In fact, every feature Robinson identifies is not only explicable on the theory that Mark didn't compose the LE (but instead a harmonizer using Mark and the other Gospels did), but more explicable, particularly as the latter theory explains far more of the content of the LE (in fact, all of it).

The SE is also far too brief to make sense from the pen of Mark: it seems to assume knowledge of the Book of Acts (e.g. Acts 1:8, and the subsequent missions to east and west depicted therein) and the Gospel of Luke (e.g. Luke 1:77). Otherwise it makes no sense, since Mark has never once mentioned 'salvation' before, much less what the 'message of salvation' is supposed to be that the Apostles then spread across the world (no such message is stated in Mark 16:5-8, for example). Likewise, Mark 16:7-8 anticipates, if anything, an appearance of Jesus, yet the SE lacks any—it simply says Jesus sent them, thus it assumes the reader is already familiar with what that means and how Jesus did that, and thus is already familiar with the NT appearance narratives in the other Gospels. This fact, combined with the lack of Markan style, condemns the SE as a forgery already from internal evidence alone.

=============

by Richard Carrier, Ph.D. (2009)

Contents[hide]

|

Introduction: Problem and Significance

If Mark did not write verses 16:9-20, but some anonymous person(s) later added those verses, pretending (or erroneously believing) that Mark wrote them (as in fact they must have), then this Gospel, and thus the Bible as a whole, cannot be regarded as inerrant, or even consistently reliable. Were those words intended by God, he would have inspired Mark to write them in the first place. That he didn't entails those words were not inspired by God, and therefore the Bible we have is flawed, tainted by sinful human forgery or fallibility. Even the astonishing attempt to claim the forger was inspired by God cannot gain credit.1 For it is so inherently probable as to be effectively certain that a real God would have inspired Mark in the first place and not waited to inspire a later forger. The alternative is simply unbelievable. And in any case, a lie cannot be inspired, nor can a manifest error, yet this material is presented as among that which is "according to Mark," which is either a lie or an error.

This has a further, even greater consequence. Since we are actually lucky the evidence of this meddling survived, we should expect that other instances of meddling have occurred for which the evidence didn't survive, calling into doubt the rest of the New Testament (hereafter NT). Since the survival of evidence is so unlikely for changes made before c. 150 A.D. (fifty to eighty years after the NT books were supposedly written), and in some cases even for changes made before c. 250 A.D. (well over a hundred more years later)—as we have few to no manuscripts of earlier date, and none complete, and scarce reliable testimonies—we can expect that many other changes could have survived undetected.2 And yet alterations in the earlier period are the most likely. For when the fewest copies existed, an emender's hope of succeeding was at its greatest, as well as his actual rate of success. Such was the case for all other books, so it should be expected for the Gospels. As Helmut Koester says, "Textual critics of classical texts know that the first century of their transmission is the period in which the most serious corruptions occur," and yet "textual critics of the New Testament writings have been surprisingly naive in this respect," despite the fact that they all agree "the oldest known archetypes" we can reconstruct from surviving manuscripts "are separated from the autographs by more than a century."3

The interpolation of the Markan ending thus refutes Biblical inerrancy. As Wilbur Pickering put it:

Are we to say that God was unable to protect the text of Mark or that He just couldn't be bothered? I see no other alternative—either He didn't care or He was helpless. And either option is fatal to the claim that Mark's Gospel is 'God-breathed'.4The whole canon falls to the same conclusion. This dichotomy is entailed by the fact of the Markan interpolation. It forces us to fall on either of two horns, yet on neither of which can a doctrine of inerrancy survive. If God couldn't protect His Book from such meddling, then he hardly counts as a god, but in any case such inability entails he can't have ensured the rest of the received text of the Bible is inerrant (since if he couldn't in this case, he couldn't in any), which leaves no rational basis for maintaining the inerrancy of the Bible, as then even God could not have produced such a thing. On the other hand, if God could but did not care to protect His Book from such meddling, then we have no rational basis for maintaining that he cared to protect it from any other errors, either, whether those now detectable or not. Since the Bible we now have can only be inerrant if God wanted it to be, and the evidence proves he didn't want it to be, therefore it can't be inerrant. It does no good to insist the Bible was only inerrant in the originals, since a God who cared to make the originals inerrant would surely care to keep them that way. Otherwise, what would have been the point? We still don't have those originals.

Only the most convoluted and implausible system of excuses for God can escape this conclusion, and any faith that requires such a dubious monstrosity is surely proven bankrupt by that very fact.

The Ending(s) of Mark

The OE, LE, and SE

Presently in the New American Standard Bible (NASB) the Gospel of Mark ends as follows (Mark 16:1-20, uncontested portion in bold):[1] When the Sabbath was over, Mary Magdalene, and Mary the mother of James, and Salome, bought spices, so that they might come and anoint Him. [2] Very early on the first day of the week, they came to the tomb when the sun had risen. [3] They were saying to one another, "Who will roll away the stone for us from the entrance of the tomb?" [4] Looking up, they saw that the stone had been rolled away, although it was extremely large. [5] Entering the tomb, they saw a young man sitting at the right, wearing a white robe; and they were amazed. [6] And he said to them, "Do not be amazed; you are looking for Jesus the Nazarene, who has been crucified. He has risen; He is not here; behold, here is the place where they laid Him. [7] But go, tell His disciples and Peter, 'He is going ahead of you to Galilee; there you will see Him, just as He told you.'" [8] They went out and fled from the tomb, for trembling and astonishment had gripped them; and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.What is commonly called (and hypothesized to be) the 'Original Ending' of Mark (OE) is presented in bold above. The material not in bold is called the 'Longer Ending' of Mark (LE). There is another ending in some manuscripts, completely replacing or preceding the lengthy text above, which reads:

[9b] Now after He had risen early on the first day of the week, He first appeared to Mary Magdalene, from whom He had cast out seven demons. [10] She went and reported to those who had been with Him, while they were mourning and weeping. [11] When they heard that He was alive and had been seen by her, they refused to believe it. [12] After that, He appeared in a different form to two of them while they were walking along on their way to the country. [13] They went away and reported it to the others, but they did not believe them either. [14] Afterward He appeared to the eleven themselves as they were reclining at the table; and He reproached them for their unbelief and hardness of heart, because they had not believed those who had seen Him after He had risen. [15] And He said to them, "Go into all the world and preach the gospel to all creation: [16] He who has believed and has been baptized shall be saved; but he who has disbelieved shall be condemned. [17] These signs will accompany those who have believed: in My name they will cast out demons, they will speak with new tongues; [18] they will pick up serpents {in their hands}, and if they drink any deadly poison, it will not hurt them; they will lay hands on the sick, and they will recover."

[19] So then, when the Lord Jesus had spoken to them, He was received up into heaven and sat down at the right hand of God. [20] And they went out and preached everywhere, while the Lord worked with them, and confirmed the word by the signs that followed.

[9a] And they promptly reported all these instructions to Peter and his companions. And after that, Jesus Himself sent out through them from east to west the sacred and imperishable proclamation of eternal salvation. Amen.This is called the 'Shorter Ending' of Mark (SE).5 Some manuscripts have neither SE nor LE (and thus have only the OE), and one manuscript contains only the SE (and that is among the oldest) while others give indications that many other such manuscripts once existed, but most (a great many in each case) have either the LE alone or both the SE and the LE (always with the LE following the SE, not the other way around, unlike the order shown in the NASB).6 The SE and LE are logically and narratively incompatible, however, and thus cannot have been composed by the same author.

The VLE

There is also a third ending found in one surviving manuscript (and already known to Jerome in the 4th century), which you generally never hear of, but which I shall call the 'Very Long Ending' (VLE), as it is an extension of the LE, expanding verse 15 into:[15] And they defended themselves saying, "This world of lawlessness and unbelief is under Satan, who does not allow the unclean things that are under the spirits to comprehend God's true power.7 Because of this, reveal your righteousness now." They said these things to Christ, and Christ replied to them, "The term of years of the authority of Satan has been fulfilled, but other dreadful things are drawing near, even to those for whose sake as sinners I was delivered up to death so they might return to the truth and no longer sin, and might inherit the spiritual and incorruptible glory of righteousness which is in heaven. But go into all the world and preach the gospel to all creation."Such are the various endings of Mark.8 All scholars now reject the VLE (if they even know of it) and now regard verse 16:8 to have been the OE, even though it is an odd way to end a book (though it is not without precedent, and does make more literary sense than is usually supposed 9). The VLE, by contrast, is unmistakably a forgery, so its existence further proves that Christians felt free to doctor manuscripts of the Gospels.

The BE

The same point is proven further by the fact that, in addition to the endings just surveyed, there is at least one known interpolation within the OE itself (expanding verse 3), extant in one ancient manuscript, which can be considered yet another 'ending' to Mark (making five altogether), the addition here given in bold:[3] They were saying to one another, "Who will roll away the stone for us from the entrance of the tomb?" Then all of a sudden, at the third hour of the day, there was darkness over the whole earth, and angels descended from heaven and [as he] rose up in the splendor of the living God they ascended with him, and immediately it was light. [4] Looking up, they saw that the stone had been rolled away, although it was extremely large.This is from Codex Bobiensis, a pre-Vulgate Latin translation, which also deletes the last part of verse 8 before attaching the SE (thus eliminating the contradiction between them: see section 4.1.3). The manuscript itself physically dates from the 4th or 5th century, but contains a text dated no later than the 3rd century, and some evidence suggests it ultimately derives from a lost 2nd century manuscript.10 No one accepts this Bobbio Ending (BE) as having any chance of being authentic, yet it must be quite ancient. It was also manifestly forged.

Assessment of the Markan Endings

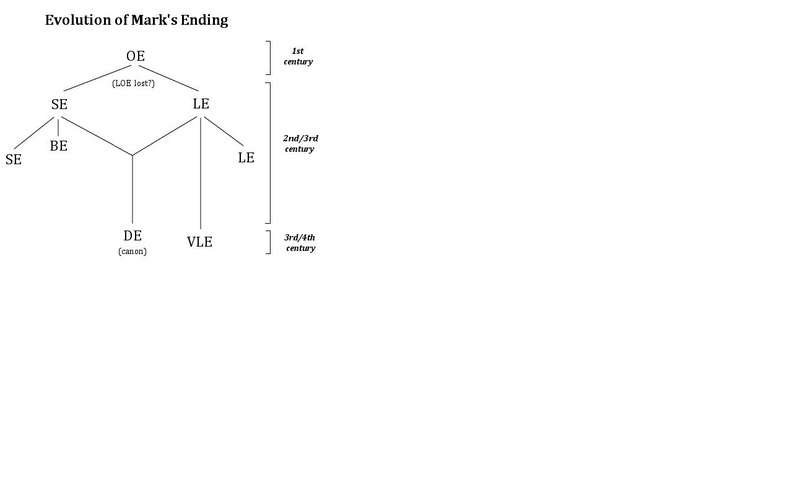

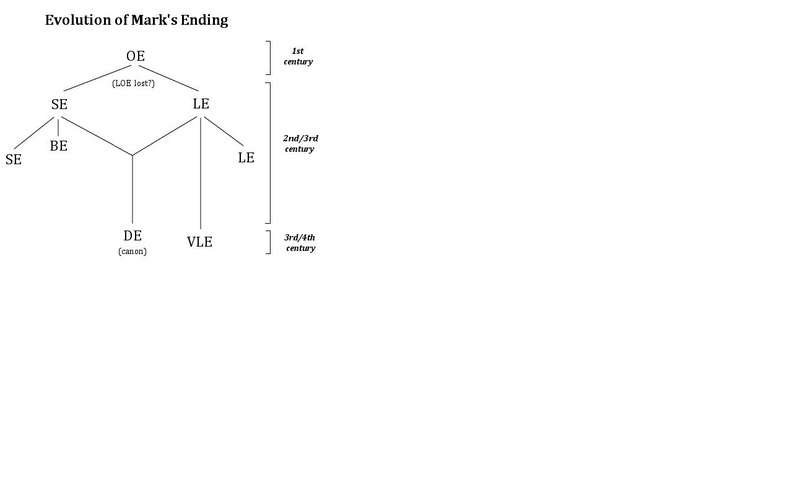

Some scholars theorize that Mark's original ending did indeed extend beyond the OE but was lost (accidentally or deliberately) and then replaced by the SE and LE in different manuscripts (hereafter mss. (plural) and ms. (singular)), originating two separate traditions which were eventually loosely combined into a sixth 'Double Ending' (DE) in later manuscripts (even though they don't logically fit together), while in other mss. the LE was preferred or was expanded into the VLE, or the OE was expanded into the BE. Though many of the arguments for a 'Lost Original Ending' (LOE) are intriguing, none are conclusive, nor can any produce the actual text of such an ending even if it existed, nor can scholars agree which ending it should be (some scholars find the original ending redacted in Matthew's Galilean mountain narrative, others in John's Galilean seashore narrative, yet others in Luke's Emmaus narrative, and still others in the SE or LE itself, and so on). I will not discuss those debates, as they are too speculative and inconclusive. It is the sole task here to demonstrate that, regardless of how Mark originally ended his Gospel, it was not the ending we have now (whether SE or LE; the DE, BE and VLE are ruled out heretofore). Quite simply, the current ending of Mark was not written by Mark.The Principal Scholarship

The literature on the ending of Mark is vast. But certain works are required reading and centrally establish the fact that the current ending of Mark was not written by Mark. They cite much of the remaining scholarship and evidence, and often go into more precise detail than I will here. So to pursue the issues further, consult the following (here in reverse chronological order):David Alan Black, ed., Perspectives on the Ending of Mark: Four Views (2008). Hereafter PEM.There are also a few online resources worth consulting (with due critical judgment). Most worthwhile is Wieland Willker's extensive discussion of the evidence and scholarship.11 Though Willker is only (as far as I can tell) a professor of chemistry, and biblically conservative, he did a thorough job of marshaling the evidence. Much briefer but still adding points of note is the treatment of the problem at Wikipedia.12 Other threads can be explored but will only end up with the same results that all the above scholars document.13

Adela Yarbro Collins, Mark: A Commentary (2007): pp. 797-818. Hereafter MAC.

Bruce Metzger and Bart Ehrman, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 4th ed. (2005): pp. 322-27. Hereafter TNT.

Joel Marcus, Mark 1-16: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (2000): pp. 1088-96. Hereafter MNT.

James Kelhoffer, Miracle and Mission: The Authentication of Missionaries and Their Message in the Longer Ending of Mark (2000). Hereafter MAM.

John Christopher Thomas, "A Reconsideration of the Ending of Mark," Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 26.4 (1983): 407-19. Hereafter JETS.

Bruce Metzger, New Testament Studies: Philological, Versional, and Patristic (1980): pp. 127-47. Hereafter NTS.

Bruce Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, 3rd ed. (1971): pp. 122-28. Hereafter TCG.

The Internal Evidence

Internal evidence is what we can conclude from the reconstructed text, such as its internal logic and literary content and style. In order of physical creation, the 'internal' evidence is earlier and so will be treated here first. Other scholars usually treat it last, but the order of examination doesn't matter. Either way, the internal evidence still confirms the LE is not by Mark, in three different ways: the SE and LE are too incongruous with the OE to have been composed by its author (i.e. the transition from the OE to either the SE or the LE is illogical); the SE and LE are written in a completely different style from Mark (which proves a different author composed them); and the LE betrays (in fact assumes) knowledge of the Canonical New Testament, which did not exist when Mark wrote (and to a lesser extent the same can be said of the SE).Transition Is Illogical

The transition from the OE to the LE violates logic and grammar, while the transition from the OE to the SE is grammatical but even more illogical. This alone greatly reduces the probability of common authorship.The LE

In the LE the transition from verse 8 to 9 is ungrammatical and thus cannot have been composed by the same author. In fact, this oddity suggests the LE actually derives from another text (possibly a 2nd century commentary on the Gospels) and was only appended to Mark by a third party. There is more evidence for this hypothesis in the manuscripts (which will be discussed later) and in every other element of this illogical transition (to be explored shortly). For the present point, it is enough to note the internal evidence. First, the grammatical subject in verse 8 is "they" (the women), but in verse 9 it is "he" (Jesus). But the word "he" is not present in verse 9. Thus we have the strange transition, "For they were afraid and having risen on the first day of the week appeared first to Mary," which makes no sense. The pronoun "he" is expected (or the name "Jesus") but it is absent, creating a strange grammatical confusion. The oddity is clearer in the Greek than in English translation. In the Greek, verse 9 begins abruptly with a nominative participle with no stated subject, a strange thing to do when transitioning from a sentence about a wholly different subject.The transition is not only ungrammatical, it is narratively illogical. Verse 9 reintroduces Mary Magdalene with information we would have expected to learn much earlier (the fact that Jesus had cast seven demons out of her). Instead it is suddenly added in the LE, completely out of the blue without any explanation, suggesting the author of the LE was trying to improve on the OE or wasn't even writing an ending to Mark but a separate narrative altogether (in which this is the first time Mary Magdalene appears in this scene or in which the story of her exorcism appeared many scenes earlier). Either entails that the same author did not write the OE. Indeed, it makes no sense to add this detail in the LE, as it serves no narrative function, adds nothing relevant to the story, and alludes to an event that Mark never relates. If the author of the LE were Mark, he would have added this exorcism story into the narrative of Jesus' ministry, and then alluded to it (if at all) when Mary Magdalene was first introduced in verse 15:40, or when she first appears in the concluding narrative (verse 16:1). Furthermore, not only does the subject inexplicably change from the women to Jesus, but suddenly Mary Magdalene is alone, without explanation of why, or to where the other two women have gone.

We should also expect some explanation of when these appearances occurred, yet we get instead an inexplicable confusion. Verse 9 says they happened after Jesus rose on the first day of the week, but it's then unclear as to how many days after. This single temporal reference would normally entail everything to follow occurred on the same day. But that would contradict the OE's declaration that Jesus had already gone ahead to Galilee and would appear there, as it would have taken several days for the women (or anyone else) to travel from Jerusalem to Galilee. It is unlikely Mark would produce such a perplexing contradiction or allow a distracting ambiguity like this in his story, as he is elsewhere very careful about marking relevant chronological progression (e.g. Mark 16:2, 15:42, 14:30, 14:12, 6:35, 4:35, etc.). Mark also wouldn't repeat the declaration that it was "the first day of the week," as he already said that in verse 16:2. Instead, he would simply say "on the same day," or not even designate the day at all, as there would be no need for it (his narrative would already imply it), until the story entailed the passage of several days (perhaps either at 16:12 or 16:14). Apparently the author of the LE assumes the day hasn't yet been stated (and thus appears unaware of the fact that it was already stated in the OE only a few verses earlier) and then assumes all these events took place over a single day, and thus in and around Jerusalem, which contradicts Mark's declaration that the appearances were to occur in Galilee (16:7, 14:28, corroborated in Matthew 28:16-20), yet conspicuously agrees with Luke and John (a telling contradiction that will be discussed later).

All four oddities (the incorrect grammar, the strange reintroduction of Mary, the unexplained disappearance of the other women, and the chronological redundancies and contradictions) make the transition from the OE to the LE too illogical for the same author to have written both. On the hypothesis that the LE was written by another author in a different book and just copied into Mark by a third party, all these oddities are highly probable. But on the hypothesis that Mark wrote the LE, all these oddities are highly improbable. Indeed, any one of them would be improbable. All of them together, very much so.

The Terry Thesis

Bruce Terry claims such odd transitions exist elsewhere in Mark and thus are not improbable, but his proposed grammatical parallels actually demonstrate what's so odd about this one, and he has no parallels for any of the other oddities.14 In Mark 2:13 we actually have a nested pericope in which the subject (Jesus) is already established at 2:1-2, and he remains the primary subject for the whole story, which story includes 2:12, which clearly explains the temporary transition of subject from Jesus to the man he healed: Jesus gives a command in v. 11, the man follows it in v. 12, then Jesus moves on in v. 13. There is no parallel here to 16:9, where Jesus has never been a subject of any prior sentence much less the whole pericope, yet suddenly he is the subject without explanation, whereas it is the women who have been the primary subject of the entire pericope up until now (beginning at 16:1), and yet even they inexplicably vanish, and suddenly all we hear about is Mary Magdalene alone. That is not a logical transition. Moreover, Mark's narrative in chapter 2 follows a clear structure of chronological stations, beginning when Jesus is introduced into the story (1:9), then sojourns in the desert (1:13), then returns to the seashore (1:14), then goes to Capernaum (1:21), then leaves (1:35) and goes through Galilee (1:39), then he returns "again" to Capernaum (2:1), where he heals the paralytic, then he returns "again" to the seashore (2:13). The structure and transitions are clear. There is nothing of the sort for 16:9. Hence the transitions in chapter 2 are logical and grammatical, but the transition at 16:8-9 is not.A similar structure accompanies Mark 6:45: the subject is already established as Jesus at 6:34, then Jesus gives commands to his Disciples to deliver food to the multitude (6:37-39), and in result the multitude eat (6:40-44), thus temporarily becoming the subject, then Jesus gives another command to his Disciples (6:45). The nested structure already has the subject clearly established as Jesus. So there is no parallel here to 16:9. The same structure accompanies Mark 7:31: the subject is already established as Jesus at 7:6, then Jesus teaches and interacts with the crowd, then heads toward Tyre and enters a house (7:24), then a woman begs his aid and they have a back-and-forth conversation (7:25-30), in which the subject shifts entirely as expected from her (7:26) to him (7:27) to her (7:28) to him (7:29) to her (7:30), and then back to him (7:31). The woman has departed in verse 7:29, so obviously we expect the subject at 7:31 to pick back up with who the primary subject has been all along: Jesus. Mark even indicates this by telling us he "again" went toward Tyre (thus leaving no mistake who the subject is). Again, there is no parallel with 16:9. In just the same way, at 8:1 we already know Jesus is the subject: he is the subject all the way up to 7:36, then we hear a brief audience reaction at 7:37, then Jesus is again the subject at 8:1, as we should already expect. In a comparable fashion, at 14:3 Jesus has already been the primary subject throughout chapter 13, then is temporarily the subject of conversation for just two verses (14:1-2), then becomes the primary subject again (14:3). There is no comparable nested structure at 16:9.

Moreover, all these alleged parallels show how different the style of the LE is, as Mark uses kai ("and") dozens of times to mark almost every transition in Mark 2 (19 out of 28 verses begin with kai), 6 (40 out of 56 verses begin with kai), and 7 (18 out of 37 verses begin with kai), yet the author of the LE shows no comparable fondness for kai (apart from two un-Markan transitions with kakainos, he begins only 1 of 12 verses with kai, and this despite the fact that the LE runs through no fewer than 9 comparable sentence transitions in just 12 verses), and more importantly, he doesn't use it to transition in 16:9, as we would expect if this is supposed to parallel the Markan style of 2:13, 6:45, 7:31, and 14:3 (which all transition with kai) as Terry claims. Only 8:1 uses instead the device of a participle-verb construction similar to 16:9, yet doesn't transition with the particle de. The LE does. And again, the subject of 8:1 was already established two verses earlier, in an obvious nested structure not at all parallel to 16:9. Another stylistic oddity comes from another verse that Terry mistakenly considers a parallel: only once, he says, does Mark elsewhere begin a new pericope with a participle, and that's at 14:66, which he claims is a parallel for 16:9. But in fact 14:66 begins with a genitive absolute, which is indeed a very Markan feature (it's also how he transitions in 8:1, another of Terry's alleged parallels). It's just that this is exactly what the author of the LE doesn't do at 16:9. Since 16:9 does not use the genitive absolute to mark its transition, but 14:66 does, even 14:66 fails to be a parallel, but instead shows just how different Mark's style was from the author of the LE.

The SE

The transition from the OE to the SE is smoother than for the LE, yet it is still too incongruous for the SE to have come from the original author. For the SE immediately contradicts the very preceding sentence (and without any explanation) by first saying the women told nothing to no one, then immediately saying they told everything to everyone, an error no competent author would commit. This was so glaringly illogical that in at least one manuscript a scribe erased the contradiction by deleting the end of verse 16:8 before continuing with 16:9a, but that ms. (designated "k" = Codex Bobiensis, Latin, 4th/5th century) is actually known for many occasions of such meddling with the text (the BE itself being an example: see section 2.3). The SE is thus even more illogical than the LE. Though otherwise a grammatically correct transition, it was clearly not written by Mark but by someone who could not accept his ending and had to change it, directly reversing what it just said. Mark would not have done that without explaining the incongruity (such as by mentioning a passage of time or otherwise indicating why the women changed their mind).Style Is Not Mark's

That the LE was clearly written by another author is also sufficiently proved by its unique style. Some examples of this were already given in section 4.1.2 (above), but the evidence is far more extensive than that. It is nearly impossible for a forger to imitate an author's style perfectly, because there are too many factors to control and no one is cognizant of even a fraction of them (from the choice and frequency of vocabulary to average sentence length, grammatical idioms, etc.). And this is entirely the case when the forger makes no effort even to try. It is also very difficult for an author to completely mask his own style, especially since authors are always unaware of all the ways in which their style differs from anyone they may be emulating. And an author never even tries to do that unless he aims to.15 Thus, if the LE was originally written in a separate work, and thus not even intended as an ending to Mark, it should exhibit a wildly different style, indicative of a different author. But if the LE was written by Mark, it should be the reverse, with far more similarities than deviations. This is not what we find.Deviations of Narrative Style

In the LE the series of events is far too rapid and terse and lacks narrative development, which is very unlike the rest of Mark, who as an author would surely cringe at the obscure, unexplained jumble of the LE. Mark composes all his pericopes with clever and elaborate literary structure, nearly everything is present for a reason and makes sense (if you understand the point of it).16 But the contents of the LE are simply rattled off like a laundry list without explanation or even a clear purpose. There is nothing in the passage that resembles the way Mark writes or composes his stories. He never rapidly fires through a laundry list of ill-described events, as if alluding to half a dozen stories not yet written. So the whole nature of the passage is starkly uncharacteristic of Mark, being "a mere summarizing of the appearances" of the risen Jesus, "a manner of narration entirely foreign" to Mark's Gospel. Indeed, as Ezra Gould had already observed over a hundred years ago, the OE's narration of "the appearance of the angels to the women is a good example of his style" and yet it's in "marked contrast" to the LE.17Even the cursory temptation scene (Mark 1:12-13) is no comparison. It still reads like a complete unit, for which we would not need or expect any further details had we not otherwise known of them (from the expansion of Matthew and Luke). The LE, by contrast, is unintelligible without knowing the details alluded to, and is not a single event, but a long compressed series of them. Never mind that each one is of phenomenally greater narrative importance than the relatively trivial fact that Jesus was once tested by the Devil. What remains inexcusably peculiar is the great number of events, compressed to so small a space—compressed so far, in fact, that each one bears even less detail than the temptation, and what details got added make no inherent sense (as will be shown in section 4.3.1). Moreover, Mark composed a unified Gospel from beginning to end, so if Mark had written the LE, we would expect the LE to mention Galilee: he has set this detail up twice already (14:28 and again in 16:7), anticipating an appearance in Galilee. So that he would drop this theme in the LE is inconceivable. Indeed, as observed in section 4.1.1 (above), the LE not only drops that theme, it contradicts it by evidently presuming a series of appearances in and around Jerusalem.

Deviations of Lexical & Grammatical Style

The stylistic evidence is alone decisive. For the vocabulary and syntax of the LE could hardly be further from the style of Mark's Gospel. This has been known for over a hundred years, most famously demonstrated to devastating effect by Ezra Gould in 1896.18 Unattributed quotations in the present section are from Gould's seminal commentary (where also the evidence is given). Following is a mere selection of the style deviations demonstrating the LE was not written by Mark:(1.) In the LE (a mere 12 verses), the demonstrative pronoun ekeinos is used five times as a simple substantive ("she," "they," "them"). But Mark never uses ekeinos that way (not once in 666 verses), he always uses it adjectively, or with a definite article, or as a simple demonstrative (altogether 22 times), always using autos as his simple substantive pronoun instead (hundreds of times).19In all, of 163 words in the LE, around 20 are un-Markan, which by itself is not unusual. What is unusual is how common most of these words normally are, or how distinctive they are of later NT writers or narratives, hence the concentration of so many of these words in the LE is already suspicious. But more damning are all the ways words are used contrary to Markan style, using different words than Mark uses or using Markan words in a way Mark never does. We also find 9 whole expressions in the LE that are un-Markan, which in just 12 verses is something of a record.

(2.) In the LE, husteron is used as a temporal ("afterward"), but never by Mark, who only uses cognates (the noun and verb) and only in reference to poverty (2 times), never to express a succession of events.

(3.) In the LE the contraction kan is used to mean "and if" but Mark only uses it to mean "even, just" (5:28 and 6:56, "if I touch even just his garment..."). Mark always uses the uncontracted kai ean to mean "and if" (8 times).

(4.) In the LE, poreuomai ("to go") is used three times, but never once in the rest of Mark (Mark only ever uses compound forms), which is "the more remarkable, as it is in itself so common a word," used 74 times in the other Gospels alone, and in Mark "occasions for its use occur on every page."

(5.) In the LE, theaomai ("to see") is used twice, but never once in the rest of Mark, who uses several other verbs of seeing instead, none of which are used in the LE. And this despite the fact that theaomai is normally a common word.

(6.) In the LE, the verb apisteô ("to disbelieve") is used twice, but never once in the rest of Mark, who always uses nominal and adjectival expressions for disbelief instead (3 times).

(7.) The LE employs blaptô ("to hurt"), a word that appears nowhere else in Mark, nor even anywhere else in the whole of the NT (except once, and there very similarly: Luke 4:35); and synergountos ("working with," "helping") and bebaioun ("to confirm"), words that appear nowhere else in Mark, nor in any Gospel (but commonplace in the epistles of Paul); and epakolouthein ("to come after," "to follow"), a word that appears nowhere else in Mark, nor in any Gospel (but used in the epistles 1 Tim. and 1 Pet.); and several other words that appear nowhere else in Mark: penthein ("to mourn"), heteros ("other"), morphê ("form"), endeka ("eleven"), parakolouthein ("accompany"), ophis ("snake"), analambanô ("take up"), and thanasimon ("deadly thing," e.g. "poison"). Not all of these novelties are unexpected, but some are.

(8.) In the LE, the expression meta de tauta ("after these things") is used twice, but never once in the rest of Mark. Among the Gospels the expression meta de tauta (or just meta tauta) is used only in John and Luke-Acts. In fact, meta tauta is so commonplace in those authors as to be stylistically distinctive of them.

(9.) In the LE, the disciples are called "those who were with him," a designation Mark never uses, and employing genomenos in a fashion wholly alien to Mark (who uses the word 12 times, yet never in any similar connotation).

(10.) The LE says "lay hands on [x]" with the idiom epitithêmi epi [x], using a preposition to take the indirect object, but Mark uses the direct dative to do that, i.e. epitithêmi [x], with [x] in the dative case (4 times). He only uses the prepositional idiom when he uses the uncompounded verb (tithêmi epi [x], 8:25). Thus Mark recognized the compound idiom was redundant, while the author of the LE didn't.

(11.) The LE employs several other expressions that Mark never does: etheathê hypo ("seen by"); pasê tê ktisei ("in the whole world"); kalôs hexousin ("get well"); men oun ("and then"); duo hex autôn ("two of them," an expression not used by Mark with any number, 'two' or otherwise); par' hês ("from whom"), which Mark never uses in any context, much less with ekballô ("cast out," "exorcise"), in which contexts Mark uses ek instead (7:27); and finally the LE uses prôtê sabbatou (16:9) where we should expect some variation of tê mia tôn sabbatôn (16:2).

(12.) The LE also lacks typical Markan words (like euthus, "early, at once" or palin, "again," and many others) while using Markan words with completely different frequencies, e.g. pisteuein ("to believe"), used only 10 times by Mark in 666 verses, in the LE is used 4 times in just 12 verses (a frequency far more typical of John, where the word appears nearly a hundred times). Any one or two of these oddities might happen in any comparably extended passage of Mark, but not so many.

Certainly, any single deviation of style will occur at the hand of the same author in any passage or verse, sometimes even several deviations of different kinds, and unique words will be common when they are distinctive to the narrative. But to have so many instances of so many deviations in such a short span of verses (against a compared text of hundreds of verses) is so improbable there is very little chance the LE was written by the same author as the rest of Mark. And the above list is but a sample. There are many other stylistic discrepancies besides the twelve just listed (and the others in section 4.1.2 above, which must be added to those twelve). James Kelhoffer surveys a vast number of them in MAM (pp. 67-122).

As Darrell Bock says, "it is the combination of lexical terms, grammar, and style, especially used in repeated ways in a short space that is the point." Hence appealing to similar deviations elsewhere in Mark fails to argue against the conclusion, which carries a powerful cumulative force matched by no other passage in Mark. This is emphasized by Daniel Wallace:

First, the most important internal argument is a cumulative argument. Thus, it is hardly adequate to point out where Mark, in other passages, uses seventeen words not found elsewhere in his Gospel, or that elsewhere he does not write euthôs for an extended number of verses, or that elsewhere he has other abrupt stylistic changes. The cumulative argument is that these 'elsewheres' are all over the map; there is not a single passage in Mark 1:1-16:8 comparable to the stylistic, grammatical, and lexical anomalies in 16:9-20. Let me say that again: there is not a single passage in Mark 1:1-16:8 comparable to the stylistic, grammatical, and lexical anomalies that we find clustered in vv. 9-20. Although one might be able to parry off individual pieces of evidence, the cumulative effect is devastating for authenticity.In fact, all the most renowned experts on this linguistic question conclude that the LE was not written by Mark and that the stylistic evidence for this is conclusive. Thus as J.K. Elliott puts it, "It is self-deceiving to pretend that the linguistic questions are still 'open'."20

The SE is even more incongruent with Markan style. Despite being a mere single verse, 8 of the 12 words in it "that are not prepositions, articles, or names" are never used by Mark—but half of them are found in the Epistles (and sometimes, among NT documents, only there).21 The whole verse consists of just 35 words altogether, 9 of which Mark never uses, in addition to several un-Markan phrases (including, again, meta de tauta). Discounting articles and prepositions and repeated words, the SE employs only 18 different words, which means fully half the vocabulary of the entire SE disagrees with Markan practice. Half the SE also consists of a complex grammatical structure that is not at all like Mark's conspicuously simple, direct style. You won't find any verse in Mark with the convoluted verbosity of "and after these things even Jesus himself from east and as far as west sent out away through them the holy and immortal proclamation of eternal salvation." The SE was clearly not written by Mark.

The Terry Thesis Revisited

Bruce Terry again claims there is nothing odd about so many unusual phrases, for even in Mark 15:42-16:6 "there are nine phrases" that appear nowhere else in Mark.22 But that's not true. Terry chooses as 'phrases' entire clauses, which obviously will be unique, since authors tend not to repeat themselves. Hence he is either being disingenuous, or he doesn't understand what a 'common phrase' is. Phrases like "after these things," "those with him," "seen by," "whole world," "get well," "and then," "[#] of them," and "from whom" are entirely generic phrases that authors tend to use frequently, or certainly often enough to expect to see them at least a few times in over six hundred verses, unless they are not phrases the author uses. Which is exactly why their presence in the LE tells us Mark didn't write it. And this conclusion follows with force because there are so many of these oddities, and some go against Mark's own preferences, e.g. using para instead of ek in "cast out from," and using prôtê sabbatou instead of tê mia tôn sabbatôn to say "first day of the week."In contrast, almost none of Terry's 'examples' are generic phrases—and what generic structure we can discern among them is often confirmed in Markan style elsewhere. For example, he claims "now evening having come" (êdê opsias genomenês) is a unique 'phrase' but what's actually generic in this phrase is êdê [x] genomenos, "now [x] having come," which Mark uses two other times (Mark 6:35 and 13:28). So this is not unique in 15:42. Likewise, Terry claims "know from" (ginôsko apo) is a unique phrase, but it's not, as Mark 13:28 has "learn from" (apo mathete), the exact same grammatical construction, just employing a different verb, while the same verb was not unknown to Mark (who used it at least three times, just never in a context that warranted the preposition). Meanwhile, "roll on" (proskulio epi) isn't a generic phrase at all—it's just an ordinary verb with preposition, and Mark uses verbs with epi to describe placing objects on things quite a lot (e.g. Mark 4:5, 4:16, 4:20, 4:21, 4:26, 4:31, 6:25, 6:28, 8:25, 13:2, 14:35), so there is nothing unique about that here, either. And there is nothing generic whatsoever about "the door of the tomb" or "white robe." These are highly specific constructions, using established Markan words. For leukos ("white") and stolê ("robe") appear elsewhere in Mark, and mnemeion ("tomb") appears two other times in Mark (and the equivalent mnêma twice as well), and thura ("door") likewise appears four other times. Likewise, "be not afraid" (me ekthambeisthe) is not a generic clause, but a whole sentence (it is an imperative declaration), none of which is unusual for Mark, who routinely uses mê for negation and uses the exact same verb (ekthambeô) in 9:15. Similarly, "come very early" (lian prôi erchomai) is not a generic phrase, either, it's just a verb with a magnified adverb of time, nor is it an unusual construction for Mark, who has "go very early" (lian prôi exerchomai) in 1:35, and who otherwise uses prôi and lian several times, and erchomai often.

That leaves only two unusual phrases in verses in 15:42-16:6: mia tôn sabbatôn, literally "on the first [day counting] from the Sabbaths" (i.e. "first day of the week") and en tois dexiois ("on the right"). The former simply paraphrases the Septuagint (Psalm 24:1), which Mark is known to do (e.g. Psalm 22 all throughout Mark 15:16-34). Only the latter is very unexpected as Mark otherwise (and quite often) uses ek dexiôn to say "on the right." So these two phrases are unique to 15:42-16:6. It's just that 2 unique generic phrases in 12 verses is simply not enough to doubt their authorship (especially when one is a quotation). But 9 unique generic phrases definitely is, especially in conjunction with all the other deviations: the Markan vocabulary that's missing, the non-Markan vocabulary that's present, the un-Markan frequencies of Markan words, and the un-Markan idioms where Mark has established a completely different practice. It is all these oddities combined that makes for a vanishingly small probability of Markan authorship. Indeed, if this is not enough evidence to establish the LE wasn't written by Mark, then we should just assume everything ever written in the whole of Greek history was written by Mark.

Agreements of Style

Though there are several Markan words and phrases in the LE, there are not enough to be peculiar. Most are words and phrases common to all authors and thus not unique to Mark. Excluding those, there are only a very few agreements with Markan style in the LE which can be considered at all distinctive. And yet there are as many agreements with the distinctive style of all the authors of the NT (including both the Gospels and Epistles)—very much unlike Mark. Kelhoffer (in MAM, pp. 121-22, 138-39) lists over forty stylistic similarities with all four Gospels (and Acts). Notably those drawn from Mark show more deviation from Markan style, using different words and phrases to say the same things, while exact verbal borrowing from the other Gospels is frequent. It is thus more probable that the LE's author was influenced by NT style as a whole (see section 4.3 next), because the similarities to Markan style are no greater than similarities to the rest of the NT, whereas the deviations from Markan style are frequent and extreme. This aspect of the LE's style is very probable if the author of the LE knew the NT, but much less probable if the LE had been written by Mark.Of course, such agreement can also be found by mere chance between any two authors. But it's even more likely when a later author has been influenced by the earlier one, and an author familiar with the whole NT could easily exhibit influence from all its authors, Mark included. This would be all the more likely if the author of the LE deliberately attempted to emulate Markan style (as a forger would be inclined to do), but if that was his intent, his effort was marvelously incompetent. For as we've seen, the disagreements of style are so enormous they far outweigh any agreement there may be. In fact, the deviations are so abundant and clear, they could argue against the original author of the LE intending it to be used as a forgery (if we assume a forger would do better). The 'forger' would then instead be some additional third party who attempted to pass off the LE as belonging to Mark. It's also possible the LE became attached to Mark by accident. But the SE can only have been a deliberate forgery, yet it deviates as much or more from Markan style, so being a lousy forgery is evidently not a valid argument against forgery. Nevertheless, I have already presented evidence (in section 4.1 above) and will present more (in following sections) that, more probably, the author of the LE did not write it as an ending to Mark but as a harmonizing summary of the appearances in all four Canonical Gospels, originally in a separate book (quite possibly a commentary on the Gospels), which was simply excerpted and attached to Mark by someone else (whether deceitfully or by accident).

Content Betrays Knowledge of the New Testament

The NT didn't exist when Mark wrote, yet the LE not only betrays knowledge of the Canonical NT (all four Gospels and Acts), it assumes the reader is aware of those contents of the NT or has access to them. As noted in section 4.2.1, this makes no sense coming from Mark, and very little sense coming from anyone at all, except someone who already knew all the stories related in the other three Gospels (and Acts) and who thus set out to quickly summarize them, knowing full well the reader could easily find those accounts and get all the details omitted here (or would already know them). Mark never writes with such an assumption. But a commentator writing a separate summary of the Gospel appearances in the NT would write something exactly like this. That the LE exhibits stylistic similarities with the whole NT, including the Epistles (as just surveyed in section 4.2), further supports the conclusion that the author of the LE knew the whole NT, and in fact was so influenced by it as to have adopted many elements of its diverse style. The author of the LE therefore cannot have been Mark.James Kelhoffer (in MAM, esp. pp. 48-155) has already extensively proved the LE used the other three Gospels (and Acts) and has refuted every critic of the notion. I will only summarize some of the evidence here. But from this and all that Kelhoffer adds, it's very improbable these elements would exist in the LE unless the author of the LE knew the Canonical NT and intended his readers to have access to it themselves.

The LE's Use of the NT

As Joel Marcus observes, the LE looks like "a compressed digest of resurrection appearances narrated in other Gospels" (MNT, p. 1090), so compressed, in fact, it "would not make sense to readers who did not know" the other Gospels and Acts. Indeed. The entire content of the LE is a pastiche of elements drawn from the three other Gospels, stitched together in a new way that eliminates contradictions among their different accounts, and written in the writer's own voice (i.e. not copying the other Gospels verbatim, but rephrasing and paraphrasing, a technique specifically taught in ancient schools):

|